If you need website work, please do get in touch

The Three Dantian points

in conV3rsions…

World Weather Visualisation

The Brexit Disaster

A New York Times commentary

in subV3rsions…

Who Owns England?

– and other stories of the proprietorship of the land

Mapping the Counties

All you ever needed to know about UK counties

Mapping London

Marissa Papen

in diV3rsions…

Origins of SARS-CoV 2

How to fall asleep in 2 minutes

If There Was Ever a Time to Activate Your Vagus Nerve, It Is Now

Four simple steps to return to a ‘rest and digest’ state

If you experience a racing heartbeat or tightness in your chest when you read a news story about the pandemic, it’s because of your sympathetic nervous system. When the brain senses a threat, it triggers the fight-or-flight response.

On the flip side, your parasympathetic nervous system plays a role in calming your body. For example, escaping from a grizzly bear and returning to your safe, cozy cave signals to the brain that the threat is gone, so the stress responds ends. Now that you’ve resolved the threat, you can return to a state of peace.

But what happens when a stressor doesn’t have a definitive ending — like, say, a pandemic that might go on for months? You could suffer some significant health consequences — unless you intervene, with the help of your nervous system.

Emerging research on the vagus nerve, a major nerve in the parasympathetic nervous system, sheds light on how people can tune in to their nervous systems and find ways back to a “rest and digest” state amidst the chronic stress.

Inhis “polyvagal theory,” psychiatrist Stephen Porges hypothesizes that the parasympathetic nervous system has two parts that cause two different responses: the dorsal vagal nerve network and the ventral vagal nerve network.

When you can’t resolve a threat through fight-or-flight (you can’t exactly run away from or physically fight a virus) or establish a social connection to help calm you, your body sometimes decides it’s better to physically and mentally “check out.” That’s called dissociation, and it’s the work of the dorsal vagal nerve network. When you’re dissociated, you’ll feel powerless and hopeless, or even depressed — that’s one reason it’s so easy to glue yourself to the couch and go numb after you hear news about the virus.

“If we can’t respond with fight-or-flight or social engagement, that’s when we might dissociate. It’s like the body has begun to decide it’s trapped,” says Aundi Kolber, a Colorado-based therapist and author of Try Softer.

The ventral vagal nerve network, on the other hand, gets activated when you’re connecting with another person (or with yourself, by responding to your body’s signs of stress), which triggers calmness. This is the part of your nervous system you want to stimulate when you’re stressed.

Emerging research on the vagus nerve sheds light on how people can tune in to their nervous systems and find ways back to a “rest and digest” state amidst the chronic stress.

Also known as the social engagement system, the ventral vagal network runs upward from the diaphragm area to the brain stem, crossing over nerves in the lungs, neck, throat, and eyes. Actions involving these parts of the body — including deep breaths, gargling, humming, or even social cues like smiling or making eye contact with someone — send messages to the brain that it’s okay to relax.

This activation can have a snowball effect. Dr. Ruth Lanius, professor of psychiatry and director of the post-traumatic stress disorder research unit at the University of Western Ontario, says activating the ventral vagus nerve also activates the prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain that deals with logic. Calming yourself allows you to think clearly and process your difficult circumstances — which will further resolve stress.

Through the ventral vagal network, you can limit the effects of stress and prevent dissociation. Here’s a four-step plan to activate it — and regain a sense of calm — when the threat of Covid-19 is overwhelming you.

Step 1: Tune into how your body feels

If you’re not aware of how your body feels when you’re stressed, it’s hard to know when you need to give your nervous system some rest and relaxation. The first step back to “rest and digest,” Kolber says, is paying attention to your body’s sensations.

Lynn Bufka, PhD, senior director of practice research and policy at the American Psychological Association (APA) recommends making note of your body’s baseline physical state when you’re calm so you can notice how stress changes your body. Go for a walk, stretch your legs, or even bend over and touch your toes, noticing what feels good and what doesn’t. “The more we recognize our bodies’ capabilities and limitations, the more we can take care of them,” she says.

Once you have a general understanding of your body’s “baseline,” you can notice the small ways stress impacts you physically. For example, you might feel your shoulders slightly tense when you read the news about the latest case numbers. Then, you can take time to relax them — an act of compassionate self-care that not only relieves physical pain but signals to your ventral vagus nerve you’re in a safe place.

Step 2: Use your breath

Whether your sympathetic or dorsal nerves are active, mindful breathing — or paying focused attention to your breath — can be a powerful way to self-regulate. Specifically, deep breathing directly stimulates the ventral vagal system, since the vagus nerve passes through the vocal cords.

Research shows that mindful, deep breathing from the diaphragm reduces cortisol, the stress hormone. In a 2017 study, people who participated in a guided breathing program — where they took, on average, four deep breaths a minute — had lower cortisol levels in their saliva immediately after the exercise.

Boston-based therapist Kimberly Schmidt Bevans says the exhale is one of the most important aspects of mindful breathing. Exhaling longer than you inhale puts the ventral vagal network into action and promotes the rest and digest response.

Step 3: Connect with people

Social connection, whether with other people or through what Kolber calls “compassionate attention” to yourself, is one of the most important ways to activate the ventral vagal network. You can’t go out with friends because of practicing social distancing, but you can FaceTime a loved one or have a meaningful conversation with someone you’re isolating with. Lanius says establishing a sense of safety and connection with someone — and making eye contact, even over a Zoom meeting — can cue your body to relax.

If there’s no one to socialize with, or if blurry, online interactions just aren’t cutting it, Schmidt Bevans says you can visualize someone you trust — even a pet — and imagine feelings of safety and connection. Or you can just hunker down in a relaxing room in your house. “If you’re stuck in your home, looking for cues of safety in your space or with another person can activate the ventral vagal system,” she says.

These things bring your body back to the present moment, which may feel safer to your nervous system than the potential scenarios of the future.

Step 4: Harness anxious thoughts

The story you tell yourself about your stressors can dictate how your body responds.

“How you interpret your situation and its danger lays out the potential for how chronic your stress will be,” says Bufka. If you know external stressors aren’t going to change anytime soon, it’s important to minimize your perception of the threat by shifting how you respond mentally.

For instance, rather than thinking about social distancing as being stuck in your house indefinitely, think about being home as a way to contribute to public health, and an opportunity to slow down.

Lanius says steering your thoughts in a more hopeful direction could cause the brain to send messages through the vagus nerve, triggering calm in all the organs and systems along the way.

One way to do that is by using your five senses. Going outside, listening to birds, and smelling a flower are all simple “grounding” activities, which Lanius says could help activate the ventral vagus nerve. Essentially, these things bring your body back to the present moment, which may feel safer to your nervous system than the potential scenarios of the future.

“If you’re actually in a dangerous situation, like getting chased by a lion, then you should run,” says Kolber. “If you’re actually safe in the present moment but your body feels like it’s threatened, grounding can calm those perceived threats.”

When you’re paying attention to both your mind and body under stress, you’ll feel more relaxed — and ultimately, more yourself. “When you’re in the hyped-up state of perceiving everything as a threat, all your resources will try to hold it together,” Bufka says. “If you try to cope with your emotional response, you’ll have more energy and resources to problem-solve.”

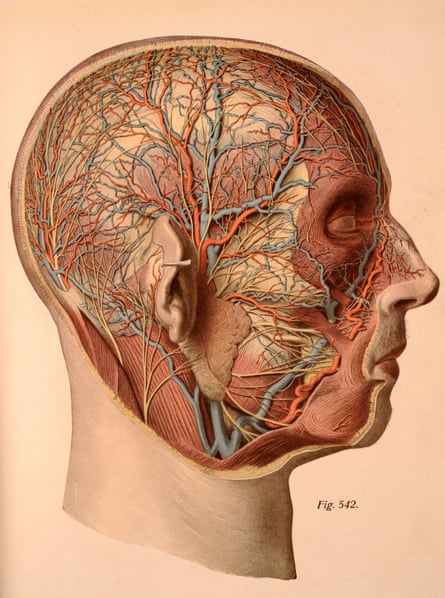

This ‘electrical superhighway’ helps to control everything from our breathing to our immune system.

Could stimulating it transform physical and mental health?

Linda Geddes

From plunging your face into icy water, to piercing the small flap of cartilage in front of your ear, the internet is awash with tips for hacking this system that carries signals between the brain and chest and abdominal organs.

Manufacturers and retailers are also increasingly cashing in on this trend, with Amazon alone offering hundreds of vagus nerve products, ranging from books and vibrating pendants to electrical stimulators similar to the one I’ve been testing.

Meanwhile, scientific interest in vagus nerve stimulation is exploding, with studies investigating it as a potential treatment for everything from obesity to depression, arthritis and Covid-related fatigue. So, what exactly is the vagus nerve, and is all this hype warranted?

The vagus nerve is, in fact, a pair of nerves that serve as a two-way communication channel between the brain and the heart, lungs and abdominal organs, plus structures such as the oesophagus and voice box, helping to control involuntary processes, including breathing, heart rate, digestion and immune responses. They are also an important part of the parasympathetic nervous system, which governs the “rest and digest” processes, and relaxes the body after periods of stress or danger that activate our sympathetic “fight or flight” responses.

In the late 19th century, scientists observed that compressing the main artery in the neck – alongside which the vagus nerves run – could help to prevent or treat epilepsy. This idea was resurrected in the 1980s, when the first electrical stimulators were implanted into the necks of epilepsy patients, helping to calm down the irregular electrical brain activity that triggers seizures.

As more people were fitted with these devices, doctors began to spot an interesting pattern. “They noticed that even if the device didn’t help their epilepsy, some of these patients started to have a better outlook on life,” says Kevin Tracey, a professor of molecular medicine and neurosurgery at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research in Manhasset, New York.

Today, vagus nerve stimulators are increasingly being investigated as an alternative to antidepressants in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Surgically implanted stimulators are also an approved treatment for epilepsy – although they only seem to work in a subset of patients.

Using electrical stimulation to treat brain disorders such as epilepsy and depression makes intuitive sense – nerves and brain cells communicate using electricity, after all.

However, in the late 1990s, Tracey and his colleagues made a surprising discovery. They were testing an experimental drug that they expected to dampen inflammation in rats’ brains, but when they injected it, it dampened inflammation throughout the body.

This was puzzling, because the brain is physically separated from the rest of the body by the blood-brain barrier – a tightly packed layer of cells that regulates the passage of large and small molecules into the brain, to help keep it safe. Tracey and his colleagues tried severing the vagus nerve and repeated the experiment. This time, the drug’s anti-inflammatory effects were confined to the brain.

It was an extraordinary discovery: conventional wisdom held that there was no connection between the nervous and immune systems – but the vagus nerve appeared to provide that link. Further research revealed that the brain communicates with the spleen – an organ that plays a critical role in the immune system – by sending electrical signals down the vagus nerve. These trigger the release of a chemical called acetylcholine that tells immune cells to switch off inflammation. Electrically stimulating the vagus nerve with an implanted device achieved the same feat.

Tracey immediately recognised the therapeutic implications, having spent years trying to develop better treatments for inflammatory conditions such as sepsis, arthritis and Crohn’s disease. Existing drugs dampen inflammation, but carry a risk of serious side effects. Here was a technique with the potential to switch off inflammation without the need for drugs.

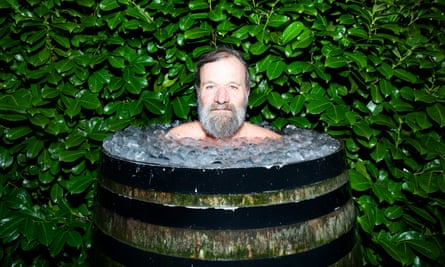

Tracey’s discovery also caught the attention of mind-body practitioners, including the Dutch motivational speaker and “Iceman” Wim Hof, who claimed that he could control inflammation in his body through a combination of breath work, meditation and cold water immersion. “He wanted me to study him,” Tracey says.

They devised an experiment that involved drawing blood from Hof before and after practising his techniques, and analysing them for markers of inflammation. To their surprise, it seemed Hof really could reduce inflammation in his body, although they required more evidence to be convinced his techniques would work in others.

Picking up the baton, Matthijs Kox at Radboud University Medical Center in the Netherlands recruited 12 volunteers to attend Hof’s training camp in Poland, where they spent 10 days swimming in icy water, rolling around in snow, meditating and learning his breathing exercises – which are characterised by a period of forced hyperventilation followed by a period of holding your breath.

Afterwards, the researchers tested the volunteers’ ability to suppress their immune responses by injecting them with a component of bacteria that triggers inflammation and flu-like symptoms. Compared with volunteers who had not undergone Hof’s training, their levels of inflammation were lower and they experienced fewer flu-like symptoms.

But were they really hacking their immune systems by tapping into the power of their vagus nerve? Yes and no. Although the volunteers were able to dampen inflammation, they released large amounts of adrenaline in the process – a key component of the fight or flight response. “This is pretty much the opposite of what you’d expect if Hof’s techniques were working through the vagus nerve,” says Kox.

Adrenaline also suppresses the immune system, but through a different mechanism. And Kox warns that repeatedly triggering these fight or flight responses could be dangerous for people with cardiovascular conditions.

Hof’s aren’t the only techniques being espoused as ways to regulate anxiety, depression and improve general health by tapping into the vagus nerve.

Search “vagus nerve hacks” on TikTok, and you’ll be bombarded with tips ranging from humming in a low voice to twisting your neck and rolling your eyes, to practising yoga or meditation exercises.

Researchers who study the vagus nerve are broadly sceptical of such claims. Though such techniques may help you to feel calmer and happier by activating the autonomic nervous system, the vagus nerve is only one component of that. “If your heart rate slows, then your vagus nerve is being stimulated,” says Tracey. “However, the nerve fibres that slow your heart rate may not be the same fibres that control your inflammation. It may also depend on whether your vagus nerves are healthy.”

Similarly, immersing your face in cold water may also slow down your heart rate by triggering something called the mammalian dive reflex, which also triggers breath-holding and diverts blood from the limbs to the core. This may serve to protect us from drowning by conserving oxygen, but it involves sympathetic and parasympathetic responses.

Electrical stimulation may hold greater promise though. One thing that makes the vagus nerves so attractive is surgical accessibility in the neck. “It is quite easy to implant some device that will try to stimulate them,” says Dr Benjamin Metcalfe at the University of Bath, who is studying how the body responds to electrical vagus nerve stimulation. “The other reason they’re attractive is because they connect to so many different organ systems. There is a growing body of evidence to suggest that vagus nerve stimulation will treat a wide range of diseases and disorders – everything from rheumatoid arthritis through to depression and alcoholism.”

In 2016, Tracey and his colleagues published the results of a study of 18 patients with rheumatoid arthritis – an autoimmune condition that causes pain, swelling and stiffness in joints – who were still experiencing symptoms despite taking immunosuppressive drugs. The patients were fitted with a vagus nerve stimulator that was used to target the fibres in their necks that are thought to control immune activity in the spleen. This led to an improvement in their symptoms and was associated with reduced levels of tumor necrosis factor, an inflammatory protein that is a leading target of drugs for rheumatoid arthritis.

Preliminary data also suggests that the technology might be effective in patients with Crohn’s disease, another inflammatory condition, which affects the digestive system.

In all of the medical conditions discussed so far, the device is implanted into the patient’s neck, where it provides regular bursts of stimulation, with different frequencies blocking or activating different nerve fibres. Although this is relatively safe, some patients do experience side effects such as fatigue or headaches.

But there may be alternative ways of stimulating the vagus nerve. Prof Chris Toumazou at Imperial College London and his colleagues are investigating whether a microstimulator could be attached to a specific branch of the vagus nerve that tells the brain when the stomach is full or empty. This idea stems from the discovery that the hormones controlling appetite communicate with the brain via the vagus nerve. Cut the nerve, and these hunger signals no longer get through.

The team has been working on a device that could eavesdrop on this chemical chatter, and send an electrical signal to the brain in response to the release of hunger hormones by an empty stomach. “The device will be able to send an opposite signal to the brain to say: ‘No, you’re full,’” Toumazou says. “We’re not completely cutting those signals off, but controlling them, which could be a much better means of obesity control than a stomach bypass.”

The device that I’ve been clipping to my ear, called a Nurosym, could provide an alternative means of stimulating the vagus nerve, and, unlike implanted stimulators, does not require surgery.

As well as organs and structures in the chest and abdomen, there’s a branch of the vagus nerve that terminates at the outer ear, known as the auricular branch.

“It projects to the brainstem and then to different regions of the brain, and that leads to vagal signalling that projects down to the heart and other organs,” says Nathan Dundovic, co-founder of London-based neurotechnology company Parasym, which develops and manufactures the Nurosym device.

Although this is primarily a medical device designed for patients with chronic health conditions that affect involuntary processes such as heart rate or digestion, Dundovic believes that healthy individuals like me may also benefit from auricular stimulation – albeit to a lesser extent.

Many of the company’s employees use the device to promote relaxation and sleep, and to potentially reap some of the cognitive enhancing effects that early clinical studies have hinted at – such as improvements in short-term memory.

Clipping the device to my tragus, the fleshy chunk of cartilage in front of my ear, I feel a gentle pulsating prickle when it is switched on. I can’t claim to have been transformed into a hyper-efficient, calmer version of myself – yet – but I’m willing to persist and see.

Not everyone is convinced that this kind of auricular vagus nerve stimulation will be clinically effective. “Because the vagus connects to so many different organ systems, it can still be a challenge sometimes to make sure that we are only stimulating the right part of the nerve,” says Metcalfe. “The idea that you can place electrodes completely outside the body and still selectively stimulate nerve fibres, I find that very hard to believe.”

However, Parasym’s device is currently being tested in trials for various heart and brain-related disorders, including postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (Pots) – a condition characterised by an abnormal increase in heart rate upon standing – and long Covid, by reputable research institutions across North America and Europe.

The idea that auricular stimulation could benefit long Covid patients is being investigated by other teams as well. Already, there is some evidence to suggest that it may help to alleviate the fatigue associated with an autoimmune disease called Sjögren’s Syndrome.

Encouraged by such findings, Dr Mark Baker at Newcastle University is now exploring whether it could also benefit patients with post-Covid fatigue.

An earlier study identified abnormalities in several areas of the nervous system – including an imbalance in the part that regulates involuntary physiological processes. “It looks a little bit like an under-functioning vagus nerve,” says Baker.

It is early days, but if researchers can find an effective way to tap into the vagus nerve – be it surgically, or through the skin – the benefits could be great.

The word vagus derives from the Latin for “wandering” – a nod to the complex and meandering path it takes through the body, and the diversity of physiological processes under its influence. Rather than popping a pill to alleviate illness, perhaps someday it will be possible to breathe, hum or zap our way to better health.